What is a "Dead Zone?"

By Beatz Alvarado

Engineers and marine biologists predict “dead zones” will form in the Inner Harbor due to daily brine dumps from proposed desalination plants.

Among them is Dr. Ben Hodges, who is an engineering professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Hodges estimates that a “dead zone” will begin to form along the bottom of the Inner Harbor within 24-48 hours of the first brine dump years from now, in 2030, when proposed desalination plants are built and begin to operate.

Two desalination plants have been proposed for the Inner Harbor: The City of Corpus Christi’s Inner Harbor Desalination Plant and Corpus Christi Polymers’ Desalination Plant.

Corpus Christi Polymers, the only private entity seeking permits to build its own desalination plant, needs a new source of water to operate what could be the largest Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plant in the world. PET is a petrochemical product often used to manufacture single-use plastics.

The Port of Corpus Christi Authority is the third key player behind efforts to bring desalination to the Coastal Bend.

What is a Dead Zone?

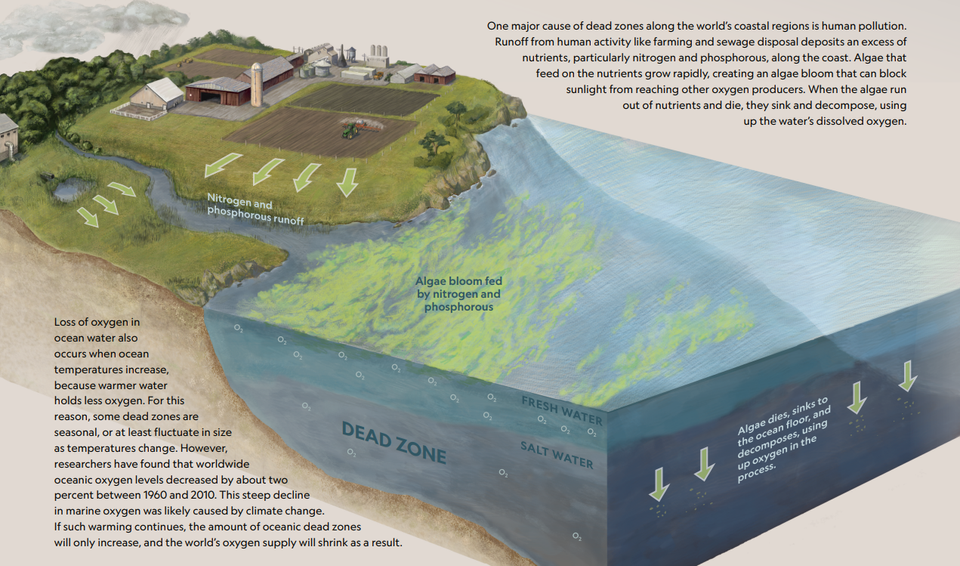

A “dead zone” begins to form as soon water becomes stratified, when heavy water separates from lighter water and falls to the bottom, Hodges told Chisme Collective.

This stratification can be caused by water that is different in temperature or salinity. In this case, salty wastewater from desal plants, or brine, would initiate stratification as soon as it’s dumped into Inner Harbor waters.

If oxygen isn’t mixed into the brine that begins accumulating along the bottom, that water will become hypoxic, Hodges said, which is a fancy term for low oxygen.

Since the heavy water has fallen to the seafloor, the only way to add oxygen would be a mechanism – like ocean currents – that creates enough energy to break up the brine, lift it off the seafloor and erode it away, he said.

That’s the problem with brine dumps into the Inner Harbor, Hodges said.

Studies have shown that the Inner Harbor does not have the mixing energy or water current to break up or dissolve the dumped industrial brine.

“(Organisms) can’t live and then everything gets really ugly down there,” Hodges said. “That’s why we call it a ‘dead zone’ because very (few organisms) can live without oxygen.”

Preventing “Dead Zones”

Hodges, who first contributed his expertise to Coastal Bend desal projects in the early 2000s, is among several proponents of a far-field model to be conducted of the Inner Harbor as a means to prevent “dead zones” in the Inner Harbor.

Running a far-field model could help avoid “dead zones” by stopping the city’s Inner Harbor desal project, as well as the Corpus Christi Polymers project, before they start.

Hodges, as well as modeling conducted by the Port of Corpus Christi Authority, indicate that once online, the plants' brine accumulation could degrade water quality beyond legal limits set by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, ultimately breaking state law when the plants are up-and-running in 2030.

In a white paper submitted to the TCEQ as part of a Contested Case Hearing Request by the Hillcrest Residents Association, Hodges states that “the lack of an inertial far-field mixing regime at this location (Inner Harbor) renders this location inappropriate for the applicant's proposal.”

“Dead Zones” & Marine Life

We spoke to Dr. Edward J. Buskey to better understand the impacts of “dead zones” on marine life in the Inner Harbor, as well as the implications of dumping brine into the Gulf of Mexico. Redirecting brine from desal plants offshore has for a long time been the preferred method for disposal of desal waste among the scientific community.

Currently, the only entity seeking permits for a desalination facility to pipe brine offshore is the Port of Corpus Christi Authority. There is minimal risk of “dead zones” forming in the Gulf of Mexico due to its volume and currents, unlike the projects proposed for the Inner Harbor.

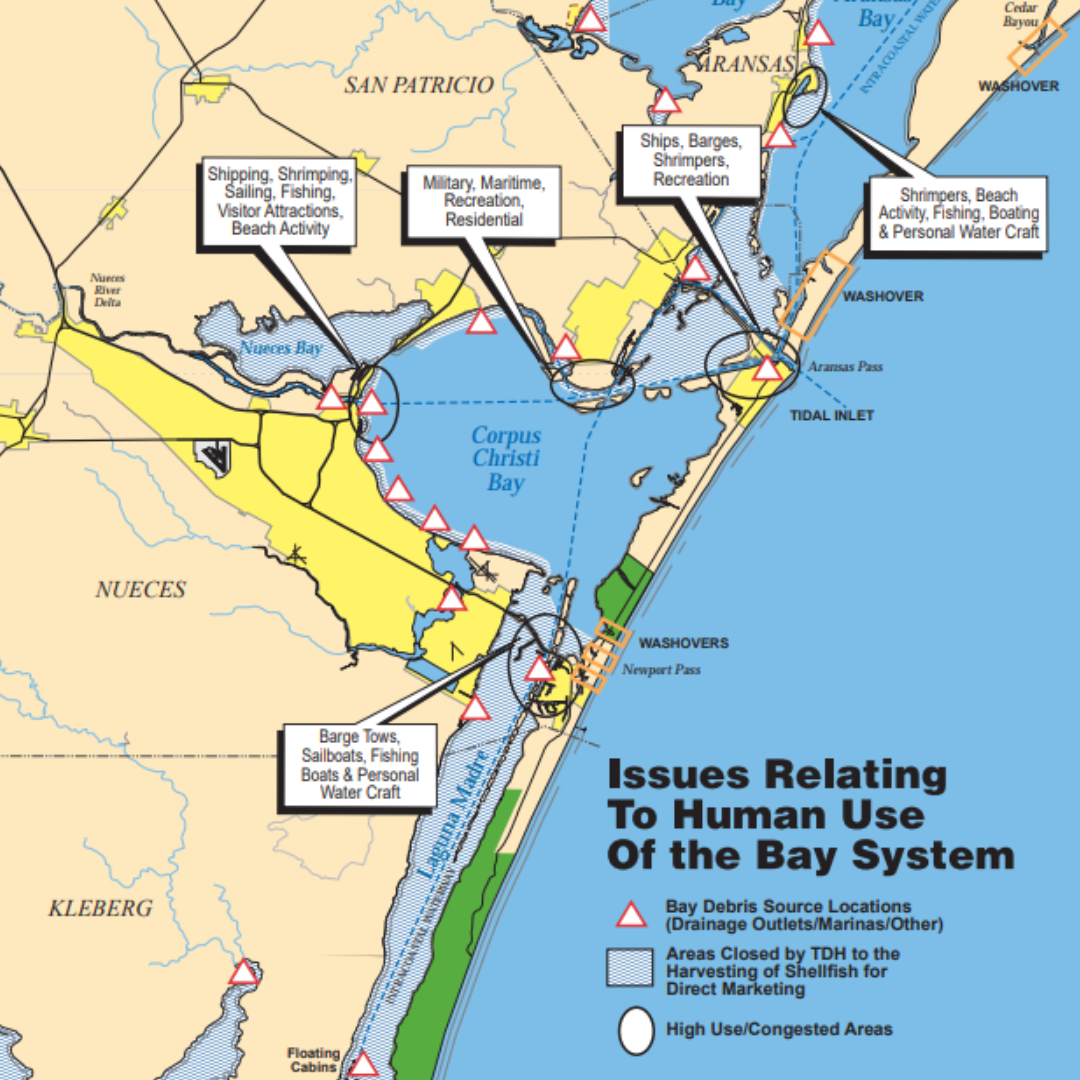

The Coastal Bend bay system, where the City and Corpus Christi Polymers projects hope to conduct daily desal brine dumps, is one of only 28 estuaries that have been designated as “Estuaries of National Significance.”

Buskey referred to estuaries as “the nursery grounds of the ocean.”

Larvae, the species that is most important to us and most vulnerable to desal brine dumps, all move into shore and into the Coastal Bend bay system as part of their lifecycle, Buskey said.

“It (a “dead zone”) will get shrimp, blue crabs, flounder, red drum, all these species that are both commercially and recreationally important,” Buskey said. “They are all what we call estuary-dependent species.”

Eggs and the larvae that are released in the Gulf of Mexico find their way back into the estuary, grow up and become adults and then go back into the Gulf, Buskey said.