Column: We Built The Refineries That Are Now Killing Us

By Julie Garcia

Another woman around my age died last month; she was from my hometown area and was diagnosed with a type of cancer that hasn’t been reported publicly. She was an artist with a brighter-than-the-sun smile. She leaves behind a husband, two daughters, her parents and brother, and a community of local artists grappling with yet another loss of a friend who died too soon.

I call it my “hometown area” because I was born in Port Arthur, Texas, went to K-12th grade in Port Neches-Groves, and I attended college in Beaumont while living in Port Arthur with my parents and older sister. The communities in Southeast Texas bleed into each other: an HEB on one side of the highway will have a Port Arthur mailing address while the Baptist church on the other side will keep a Nederland one.

Sometimes called the Golden Triangle, Beaumont, Port Arthur and Orange are the three biggest towns in the area. Between them, there is one university and two state colleges and more than 10 school districts. I spent my formative years in what locals call Mid-County, which is Port Neches, Groves and Nederland. Have you ever heard of Mid-County Madness, the high school rivalry game between PN-G and Nederland? I’m sure you’ve seen a video or two of PN-G’s continued racist use of a mascot modeled after stereotypical Native American culture – with lots of purple-and-white.

My mother’s family, the Mezas, have a family tree going back to the 1720s in Mexico. We came to the Americas from Spain like many others with a land grant and cattle. Back then, we were the Borregos, and Mexico wasn’t an independent country yet. By the late 1790s, an ancestor, Jose Borrego, immigrated to Laredo (which was part of then-Spanish Mexico). My people stayed in the Laredo area after it became part of the United States, then the Republic of Texas, and finally the state of Texas. What I’m saying is soy Tejana.

In the early 1940s, my mother’s people immigrated to Southeast Texas, namely Port Neches, to help build and work in the Texaco petrochemical refinery during the second World War. About 40 years prior, oil exploded from the earth in Beaumont (then-called Spindletop); it was very “There Will Be Blood,” and the Southeast Texas petrochemical industry was created. And that’s why my family ended up here. My mother’s father, Benito, and many other Mexican-American men were recruited by oil executives to come to the area with their wives and children to have a lifetime job in the refineries. It was a stable paycheck for the men, many of whom had families of 10 or more children (my mother is one of 10 siblings) and an opportunity to assimilate their lighter-complected Hispanic children in a nearly all-white community.

My grandfather worked for the refinery for more than 25 years. He died in 1974 from what doctors called asbestosis, a lung disease caused by inhaling asbestos fibers over many years which causes scarred lung tissue. He died in my family’s home, suffering for years, trying to find his breath. The disease is often associated with mesothelioma cancer.

My mother still owns that home, our heirloom property on Avenue D. She grew up with the younger half of her sibling brood there; hosted Thanksgiving and Christmas for the family there; she raised my sisters and me there. When I picture “home,” I picture my house on Avenue D; next door were my beloved neighbors and longtime family friends, Tia Elvira and Tio Felipe. They were recruited to work in the refineries from San Ignacio, Texas. Their children were best friends with my mom and aunts and uncles. Tia Elvira’s granddaughter, Sara, was one of the first friends I ever made. Less than a mile from our home stands what was most recently TPC Group. You may have read about the 2019 Thanksgiving Day TPC explosion in Port Neches – it blew out our windows and spewed toxic chemical fumes in the air for days on end.

I didn’t mean for this column to become a history lesson. But you must know that our people made this place; we created this industry; we built these refineries and many fathers and grandfathers have lost their lives in the process and aftermath.

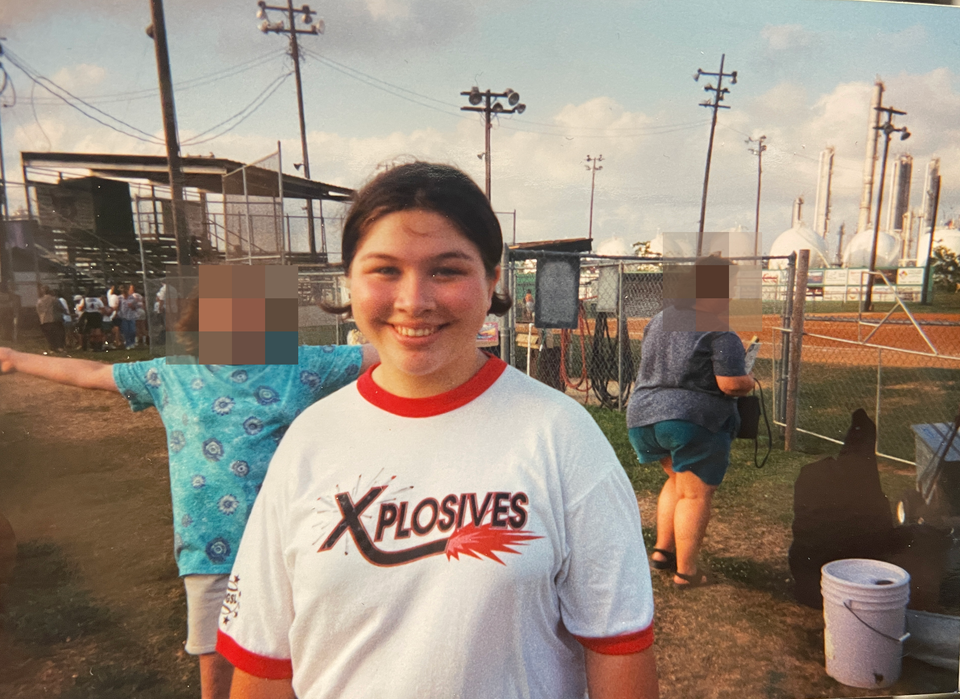

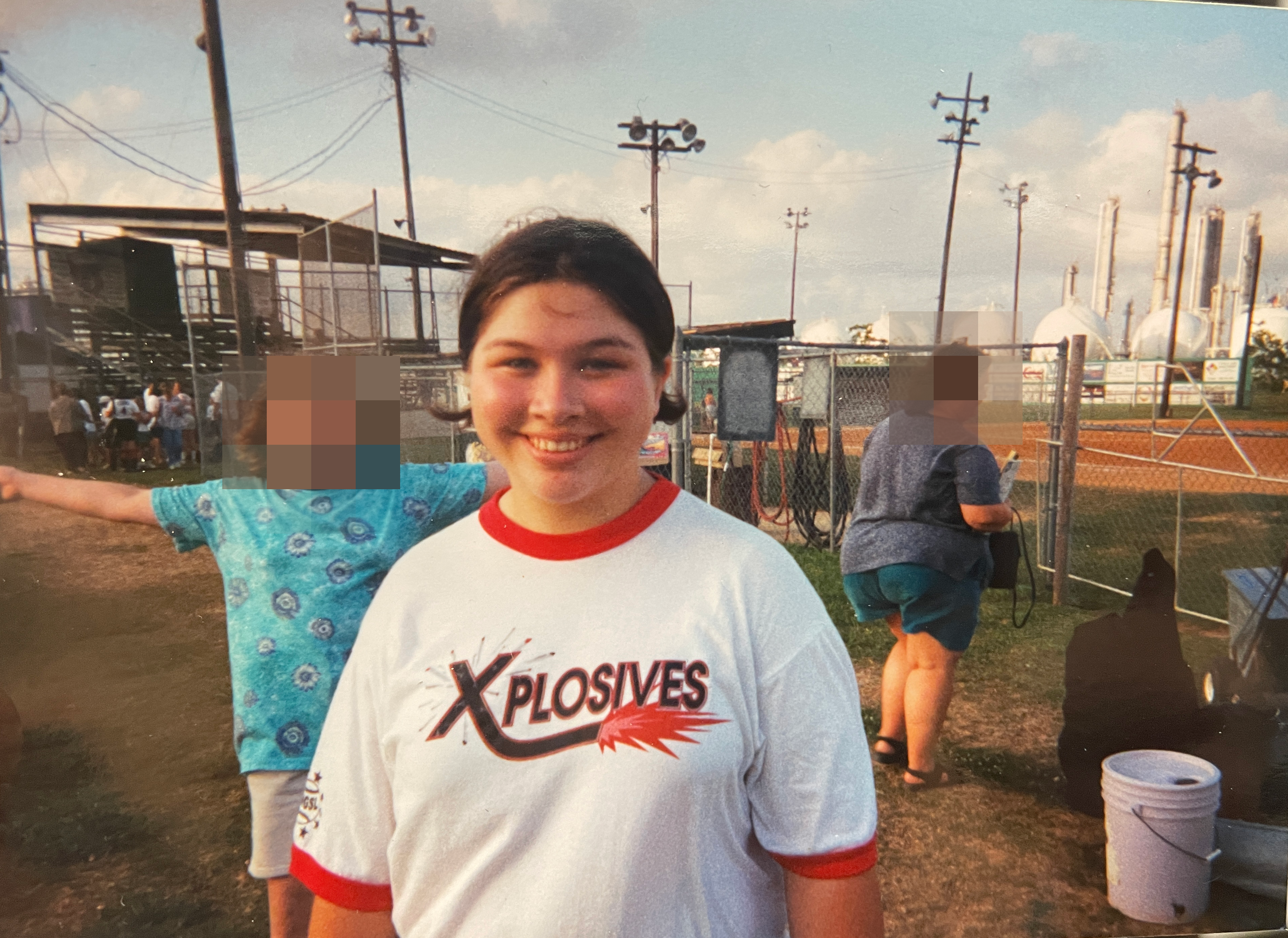

Eighty years later, and my generation is paying a heavy and devastating price for the development of the petrochemical industry in Southeast Texas. I graduated from high school in 2005, and I wish I could count how many of my classmates have been diagnosed with their first bouts of cancer. Two of my best friends suffered from thyroid issues in their early 30s, and one of them had to undergo multiple surgeries and radiation to survive. Her soccer teammate died from tongue and throat cancer when we were in our mid-20s. A local pageant mom in her early 40s is battling a rare form of cancer currently, and there have been fundraisers to raise money for her travels to MD Anderson Cancer Center. Where I’m from, many young children die from cancer, or they are diagnosed with rare and debilitating diseases early in life. In 1981, Texas Monthly ran a story called “The Cancer Belt,” detailing the instances of cancer in Port Neches and surrounding towns with refineries. At the time of the story’s publication, my eldest sister was 7, my middle sister was a 1-year-old, and I was born six years later. Instances of cancer are not new in my hometown, but for some reason, that hasn’t scared off the people who continue to live there.

However, Southeast Texas is not the dirtiest or most polluted industrial area to grow up in. Since the mid-20th century, it has grown exponentially with retail, restaurants, education and nightlife while retaining much of that small-town charm that locals love: festivals, church revivals, Little League games, Friday night football and trunk-or-treats for Halloween.

I’m 37-years-old and living in Houston. As a newspaper journalist, I moved to Victoria, Texas, Corpus Christi, Lansing, Michigan, and then back to Corpus Christi. I’ve lived in Houston now for five years.

As I drive the streets of my East End neighborhood, especially as the roads wind deeper into Magnolia Park and Pecan Park, I notice the parallels to my hometown. Due to the area’s proximity to the Port of Houston and Buffalo Bayou, those two neighborhoods are at the edge of what is called The Loop, meaning it is inside the loop of Interstate-610.

On the opposite side of I-610 is the Harrisburg / Manchester / Smith Addition. Though less than a mile away from the East End, this addition is a hotbed of refinery-like activity with at least 10 industrial companies housed within three miles of each other near the Port and the bayou.

I hope to live to see the day when our lives aren’t bartered for more jobs and the promise of a thriving economy. I hope to live to see the day when my great-niece (who will be born close to Dec. 25 this year) graduates from high school, and then college, and then maybe has a niece of her own.

Regardless of where we live, our families deserve to be multigenerational; our loved ones should not have to be tragic stories whispered between cousins or photos lost in an album. We deserve to live good, healthy lives.